OPINION: An enlightening book on the founding of Pinoy journalism

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

OPINION: An enlightening book on the founding of Pinoy journalism

John Paul 'JP' Tanchanco -- JPnomics

Published Jul 28, 2018 05:37 PM PHT

Would the founders of Pinoy journalism and media be proud of us today?

Would the founders of Pinoy journalism and media be proud of us today?

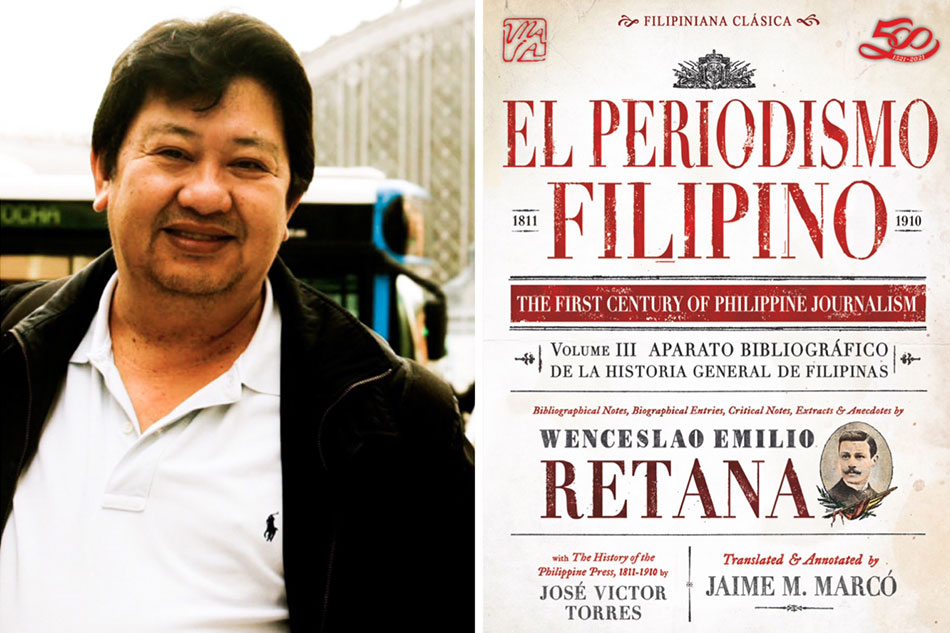

In this age of digital and social media, Filipino-Spanish historian Mr. Jaime Marco and Palanca award winner Dr. Jose Victor Torres, together with Vibal, released a book about the history of Pinoy journalism entitled "El Periodismo Filipino".

In this age of digital and social media, Filipino-Spanish historian Mr. Jaime Marco and Palanca award winner Dr. Jose Victor Torres, together with Vibal, released a book about the history of Pinoy journalism entitled "El Periodismo Filipino".

I had a chat with Jaime Marco about his new project. The last time we talked about history was when I featured him in 2012 when I visited Madrid, Spain to document the different historical markers of the Rizal walking tour which he founded there.

I had a chat with Jaime Marco about his new project. The last time we talked about history was when I featured him in 2012 when I visited Madrid, Spain to document the different historical markers of the Rizal walking tour which he founded there.

El Periodismo Filipino

The book has been released and is available thru shop.vibalgroup.com.

The book has been released and is available thru shop.vibalgroup.com.

ADVERTISEMENT

El Periodismo Filipino contains important documents from Spanish scholar and critic Wenceslao E. Retana. It documents a century of journalistic endeavors that capture the struggle of Filipinos to express themselves freely and independently during the reform movement of the 1800s.

El Periodismo Filipino contains important documents from Spanish scholar and critic Wenceslao E. Retana. It documents a century of journalistic endeavors that capture the struggle of Filipinos to express themselves freely and independently during the reform movement of the 1800s.

According to Marco, Retana's book is comprised of “bibliographical notes, biographical entries, critical notes, extracts, and anecdotes” that make up a fascinating potpourri of Filipino intellectual thoughts as it travels from ignorance to tentative expressions of identity, then to bold radicalism and freethinking.

According to Marco, Retana's book is comprised of “bibliographical notes, biographical entries, critical notes, extracts, and anecdotes” that make up a fascinating potpourri of Filipino intellectual thoughts as it travels from ignorance to tentative expressions of identity, then to bold radicalism and freethinking.

"This was originally written in Spanish which I translated and annotated but in the process of doing so, it was interesting to find out that the Filipinos were already conscious of their rights and free speech as well as racial equality. Refer to page 8 note 23. El Indio Agraviado was so important that Retana reprinted it," explained Marco.

"This was originally written in Spanish which I translated and annotated but in the process of doing so, it was interesting to find out that the Filipinos were already conscious of their rights and free speech as well as racial equality. Refer to page 8 note 23. El Indio Agraviado was so important that Retana reprinted it," explained Marco.

Finally bursting forth in the Revolution of 1896, the book reveals how Filipino republican ideals were shattered once again by yet another devious colonial master.

Finally bursting forth in the Revolution of 1896, the book reveals how Filipino republican ideals were shattered once again by yet another devious colonial master.

Retana relates wittingly in the book that initially, journalism was very exclusive and controlled as the Spaniards did not want corruption and turmoil around the world to affect their colonial slaves.

Retana relates wittingly in the book that initially, journalism was very exclusive and controlled as the Spaniards did not want corruption and turmoil around the world to affect their colonial slaves.

ADVERTISEMENT

"Colonial print was initially addressed only to the Spanish elite, the peninsulares who were deeply disturbed due to the turmoil unleashed in Spain by Napoleon’s overthrow of the monarchy. The historic developments unleashed by the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812 reverberated for a century in the Philippines, setting off vociferous debates between the forces of modernity and conservatism," he said.

"Colonial print was initially addressed only to the Spanish elite, the peninsulares who were deeply disturbed due to the turmoil unleashed in Spain by Napoleon’s overthrow of the monarchy. The historic developments unleashed by the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812 reverberated for a century in the Philippines, setting off vociferous debates between the forces of modernity and conservatism," he said.

It is evident from the historical accounts collated that the birth of local journalism show the love and passion of ilustrados, mestizos, Indios and principalias to educate and enlighten their community about religious fraud, corruption, human rights and good governance. It inspired underground Philippine newspapers to come out. This was possible thru the rise of privately owned printing presses.

It is evident from the historical accounts collated that the birth of local journalism show the love and passion of ilustrados, mestizos, Indios and principalias to educate and enlighten their community about religious fraud, corruption, human rights and good governance. It inspired underground Philippine newspapers to come out. This was possible thru the rise of privately owned printing presses.

"The rise of privately owned printing presses led to the earliest Philippine newspapers and the eruption of a vigorous and free public debate among the peninsulares, insulares, mestizos, and indios."

"The rise of privately owned printing presses led to the earliest Philippine newspapers and the eruption of a vigorous and free public debate among the peninsulares, insulares, mestizos, and indios."

The journalists and their projects helped found an era of freedom, human rights and free thinking that developed following religious colonial censorship of mass media.

The journalists and their projects helped found an era of freedom, human rights and free thinking that developed following religious colonial censorship of mass media.

"This rambunctious state of affairs led to repression of the colonial government, which sought to rein in the mushrooming 'phantasms' of the liberal and progressive kind through the imposition of a press censorship board in 1856 that was controlled in the majority by Spanish regular clergy, thus giving them an inordinate influence on the circulation of ideas."

"This rambunctious state of affairs led to repression of the colonial government, which sought to rein in the mushrooming 'phantasms' of the liberal and progressive kind through the imposition of a press censorship board in 1856 that was controlled in the majority by Spanish regular clergy, thus giving them an inordinate influence on the circulation of ideas."

ADVERTISEMENT

True soul of Pinoy sovereign journalism

In the book, we witness print culture slipping away from two and a half centuries of Spanish friar control, which previously had only emphasized translation and doctrinal dissemination. The nascent colonial press controlled by both public and religious authorities gave rise--for the first time--to a “reading public” that led to a third sphere of opinion, thus setting the stage for ambivalence, insubordination, and conflict.

In the book, we witness print culture slipping away from two and a half centuries of Spanish friar control, which previously had only emphasized translation and doctrinal dissemination. The nascent colonial press controlled by both public and religious authorities gave rise--for the first time--to a “reading public” that led to a third sphere of opinion, thus setting the stage for ambivalence, insubordination, and conflict.

Historical facts show that print culture was initially mouthpieces of elite colonial Spaniards and religious masters, who would rather make Filipinos focus on their daily religious rituals and dogmas than become aware of real life in the country and the world.

Historical facts show that print culture was initially mouthpieces of elite colonial Spaniards and religious masters, who would rather make Filipinos focus on their daily religious rituals and dogmas than become aware of real life in the country and the world.

But then the Philippine press grew amidst political divisions to become a site of contestation between the regime and growing and increasingly nationalistic class of indio, mestizos, and hijos del país who were supported by their liberal Spanish sympathizers.

But then the Philippine press grew amidst political divisions to become a site of contestation between the regime and growing and increasingly nationalistic class of indio, mestizos, and hijos del país who were supported by their liberal Spanish sympathizers.

"Fake news is not new. Just as much as I would like to leave this information readable to Filipinos, I would like Filipinos to be able to appreciate how we had fought to come up with great journalistic standards [with people] like Epifanio de los Santos, Amtonio Luna, Isabelo de los Reyes, Pascual Poblete, Fernando Maria Guerrero,Graciano López Jaena, etc. These people stood up against all odds to assure that we enjoy our freedom of speech today. But are we really using that freedom correctly? I don’t think so as many are using journalism to manipulate the way of thinking of so many people. We can see this in the US with the rise of xenophobia which is filtered through some journalistic sources.

"Fake news is not new. Just as much as I would like to leave this information readable to Filipinos, I would like Filipinos to be able to appreciate how we had fought to come up with great journalistic standards [with people] like Epifanio de los Santos, Amtonio Luna, Isabelo de los Reyes, Pascual Poblete, Fernando Maria Guerrero,Graciano López Jaena, etc. These people stood up against all odds to assure that we enjoy our freedom of speech today. But are we really using that freedom correctly? I don’t think so as many are using journalism to manipulate the way of thinking of so many people. We can see this in the US with the rise of xenophobia which is filtered through some journalistic sources.

"From translating and annotating this book, I learned that our forefathers fought to enlighten our nation, thinking it was the right path to independence. Now, whether we have appreciated this is for people to judge by the way they obtain and understand information," said Marco.

"From translating and annotating this book, I learned that our forefathers fought to enlighten our nation, thinking it was the right path to independence. Now, whether we have appreciated this is for people to judge by the way they obtain and understand information," said Marco.

ADVERTISEMENT

La Independencia

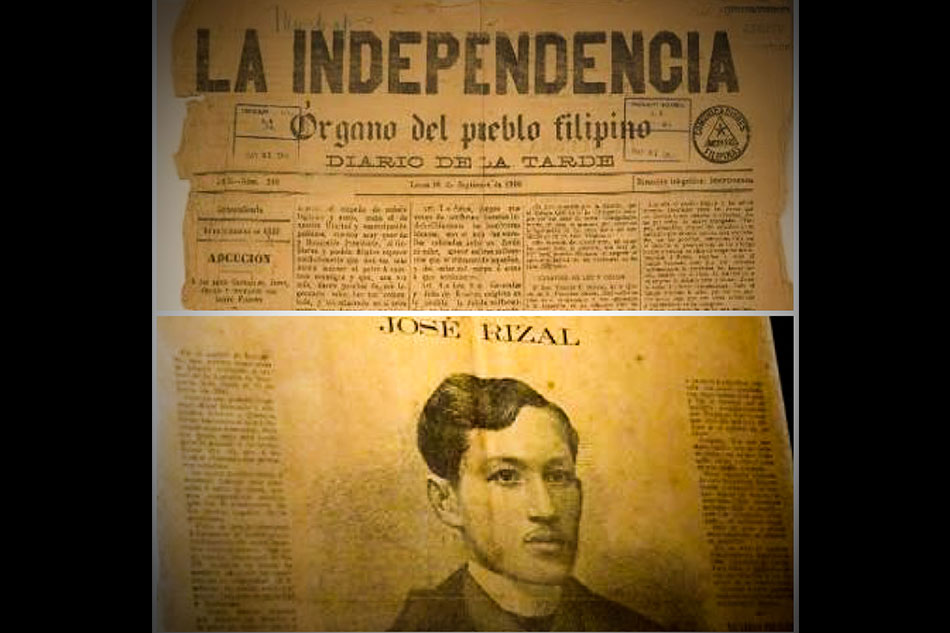

La Independencia was the first Filipino newspaper.

La Independencia was the first Filipino newspaper.

Marco said the book has an overview of the La Independencia, which could tickle the fancies of media followers, collectors and history buffs.

Marco said the book has an overview of the La Independencia, which could tickle the fancies of media followers, collectors and history buffs.

"In the book, you will also find an overview of La Independencia which was our first Filipino independent newspaper. It was the organ of the revolution. It started printing in Malabon and later moved to Malolos. As the government started losing ground, they loaded the machines on a train and started printing in Tarlac until they ended up in Pangasinan where they had to bury all the material so the Americans would not capture them," said Marco.

"In the book, you will also find an overview of La Independencia which was our first Filipino independent newspaper. It was the organ of the revolution. It started printing in Malabon and later moved to Malolos. As the government started losing ground, they loaded the machines on a train and started printing in Tarlac until they ended up in Pangasinan where they had to bury all the material so the Americans would not capture them," said Marco.

Geo-Political and Language Barriers

The book also shows that our thought-leaders and the youth should also awaken to the fact that there are other historical information that make up the identity of the Philippines as a country that have still been unrecognized because of diverse language barriers in different countries.

The book also shows that our thought-leaders and the youth should also awaken to the fact that there are other historical information that make up the identity of the Philippines as a country that have still been unrecognized because of diverse language barriers in different countries.

"As you know, I had lived in Spain for 33 years. Returning to the Philippines was a very big decision I was faced with. While in Spain, I had done a lot of research on Philippine history to finally see that many Filipinos do not appreciate their identity because of lack of firsthand information which had not been manipulated. I had read a lot of book about our history which were all documented in Spanish. These books as well as all the documentation I had read in Spanish archives made me understand our identity as Filipinos which I am so proud of. Our nation flourishes with great minds who spend their lives in trying to achieve the true greatness of our country because one way or another they have come to terms with our identity. With this book and the future books I will translate, I would like to share with our countrymen the way I got to understand and be proud of our identity," he said.

"As you know, I had lived in Spain for 33 years. Returning to the Philippines was a very big decision I was faced with. While in Spain, I had done a lot of research on Philippine history to finally see that many Filipinos do not appreciate their identity because of lack of firsthand information which had not been manipulated. I had read a lot of book about our history which were all documented in Spanish. These books as well as all the documentation I had read in Spanish archives made me understand our identity as Filipinos which I am so proud of. Our nation flourishes with great minds who spend their lives in trying to achieve the true greatness of our country because one way or another they have come to terms with our identity. With this book and the future books I will translate, I would like to share with our countrymen the way I got to understand and be proud of our identity," he said.

ADVERTISEMENT

Founders of the Pinoy Press

According to Marco, many principalias and Pinoy mestizo families from Bulacan and Malolos helped capitalize the founding of the industry as the center of printing moved from Malabon to Malolos, which then became first constitutional republic in Asia.

According to Marco, many principalias and Pinoy mestizo families from Bulacan and Malolos helped capitalize the founding of the industry as the center of printing moved from Malabon to Malolos, which then became first constitutional republic in Asia.

"The great majority of them (investors) were from the principalia. You need a certain amount of education and capital to be able to write," he said.

"The great majority of them (investors) were from the principalia. You need a certain amount of education and capital to be able to write," he said.

In the book, Retana documents numerous engaging stories, including that of a private printing press owned by Doña Remigia Salazar, the first Filipina printer and publisher.

In the book, Retana documents numerous engaging stories, including that of a private printing press owned by Doña Remigia Salazar, the first Filipina printer and publisher.

There was a publishing duo composed of Francisco Calvo and Marcelo del Pilar who jointly established a left-liberal mouthpiece; Isabelo de los Reyes, founder of the first thoroughly Filipino periodical; and, José Anacleto Ramos Ishikawa, a wealthy English-educated mestizo who fronted a fine bookstore-cum-subversive literature purveyor.

There was a publishing duo composed of Francisco Calvo and Marcelo del Pilar who jointly established a left-liberal mouthpiece; Isabelo de los Reyes, founder of the first thoroughly Filipino periodical; and, José Anacleto Ramos Ishikawa, a wealthy English-educated mestizo who fronted a fine bookstore-cum-subversive literature purveyor.

Marco also described the work of Dr. Jose Victor Torres in the book.

Marco also described the work of Dr. Jose Victor Torres in the book.

ADVERTISEMENT

"He is an outstanding Filipino historian on journalism. He consolidated Retana's entries into one clear picture of the development of Filipino intellectual thought. While I translated the text, he told the story for readers to get a clearer picture of the involvement of Filipinos in the press of that time.

"He is an outstanding Filipino historian on journalism. He consolidated Retana's entries into one clear picture of the development of Filipino intellectual thought. While I translated the text, he told the story for readers to get a clearer picture of the involvement of Filipinos in the press of that time.

"Victor is the expert on the history of Filipino journalism. What I translated would not have been as interesting to a non-Filipino historian. But with the overview and analysis he made, it now becomes very interesting to know how all that happened by reading my work," he said.

"Victor is the expert on the history of Filipino journalism. What I translated would not have been as interesting to a non-Filipino historian. But with the overview and analysis he made, it now becomes very interesting to know how all that happened by reading my work," he said.

Dr. Torres of DLSU on the founding of La Solidaridad

Alongside these tales, we witness printing innovations such as the first illustrated weekly, Ilustracion Filipina, and the rise of a cadre of print workers of editors, managers, typesetters, lithographers, and engravers who would coalesce into a radical organization for change.

Alongside these tales, we witness printing innovations such as the first illustrated weekly, Ilustracion Filipina, and the rise of a cadre of print workers of editors, managers, typesetters, lithographers, and engravers who would coalesce into a radical organization for change.

To combat the established wardens of ecclesiastical authority and anti-modernity, a ragtag group of indio and mestizo ilustrados apprenticed themselves to their Spanish mentors as impressionable chicos de la prensa or press boys who aspired to hone their journalistic skills and express their voices.

To combat the established wardens of ecclesiastical authority and anti-modernity, a ragtag group of indio and mestizo ilustrados apprenticed themselves to their Spanish mentors as impressionable chicos de la prensa or press boys who aspired to hone their journalistic skills and express their voices.

In the book, we also encounter young Isabelo de los Reyes, fiery Marcelo del Pilar, indignant Felipe Calderón, and well-meaning but hapless Pascual Poblete, along with the author himself who is consumed with jealousy as his mentor, the great dean of Philippine journalism D. José Felipe Del-Pan, who attended to his native protégés with preferential dedication.

In the book, we also encounter young Isabelo de los Reyes, fiery Marcelo del Pilar, indignant Felipe Calderón, and well-meaning but hapless Pascual Poblete, along with the author himself who is consumed with jealousy as his mentor, the great dean of Philippine journalism D. José Felipe Del-Pan, who attended to his native protégés with preferential dedication.

ADVERTISEMENT

"El Periodismo Filipino" traces the native and mestizo voices joined to the incipient struggle for native clerical rights that was launched by the brilliant Fr. Pedro Peláez who died an untimely death.

"El Periodismo Filipino" traces the native and mestizo voices joined to the incipient struggle for native clerical rights that was launched by the brilliant Fr. Pedro Peláez who died an untimely death.

However his young protégé, Fr. José Burgos, transformed Peláez’s campaign into a broad crusade for racial equality that was aided by Spanish thinkers such as Miguel Morayta, Segismundo Moret, Antonio Maura, Rafael María de Labra, and Francisco Pi y Margall.

However his young protégé, Fr. José Burgos, transformed Peláez’s campaign into a broad crusade for racial equality that was aided by Spanish thinkers such as Miguel Morayta, Segismundo Moret, Antonio Maura, Rafael María de Labra, and Francisco Pi y Margall.

As events inexorably explode into the Philippine Revolution of 1896, Retana documents the highest ideals and principles of the first independent Asian republic, which are squelched by the irruption of a more deadly imperialist, the United States of America.

As events inexorably explode into the Philippine Revolution of 1896, Retana documents the highest ideals and principles of the first independent Asian republic, which are squelched by the irruption of a more deadly imperialist, the United States of America.

Recognizing the founding Values

Marco also describes that there are still many values preserved in the Philippine press and social media that the founders would be proud about.

Marco also describes that there are still many values preserved in the Philippine press and social media that the founders would be proud about.

"We have very brave journalists despite the fact that we have one of the highest number of journalists killed to defend what they think is good for our country. Though there is actually very little critical writing in the traditional press today. The only criticisms now come from social media. We had great critical writers like Isabelo de los Reyes and Pascual Poblete who was the founder of many progressive newspapers, like El Bello Sexo, page 165 which was the first feminist newspaper. He used Spaniards as a front to set up newspapers. El Resumen was supposed to be the spokesperson of Rizal. There’s a long meditation of this on page 155. Retana basically claims Rizal was writing for Poblete which actually nobody knows until now. The book goes into an extended study of this assertion . There is a very good analysis on pages 156-157," he explained.

"We have very brave journalists despite the fact that we have one of the highest number of journalists killed to defend what they think is good for our country. Though there is actually very little critical writing in the traditional press today. The only criticisms now come from social media. We had great critical writers like Isabelo de los Reyes and Pascual Poblete who was the founder of many progressive newspapers, like El Bello Sexo, page 165 which was the first feminist newspaper. He used Spaniards as a front to set up newspapers. El Resumen was supposed to be the spokesperson of Rizal. There’s a long meditation of this on page 155. Retana basically claims Rizal was writing for Poblete which actually nobody knows until now. The book goes into an extended study of this assertion . There is a very good analysis on pages 156-157," he explained.

ADVERTISEMENT

About Jaime Marco y Marquez

The first time I interviewed Jaime Marcó y Márquez was in Madrid in 2011. He is a life-long Rizalista and Retanista.

The first time I interviewed Jaime Marcó y Márquez was in Madrid in 2011. He is a life-long Rizalista and Retanista.

He was schooled in Colegio de San Juan de Letrán, and he migrated to Spain where he established several language schools. During his time there, he organized the expatriate Filipino community and started the Jose Rizal walking tour.

He was schooled in Colegio de San Juan de Letrán, and he migrated to Spain where he established several language schools. During his time there, he organized the expatriate Filipino community and started the Jose Rizal walking tour.

He was instrumental in laying commemorative cornerstones in Madrid to mark significant milestones of Philippine history, aided by the Philippine Embassy and the Ayuntamiento de Madrid. He is presently translating Retana’s other landmark works, Vida y Escritos del Dr. José Rizal and the massive Aparato Bibliográfico de la Historia General de Filipinas.

He was instrumental in laying commemorative cornerstones in Madrid to mark significant milestones of Philippine history, aided by the Philippine Embassy and the Ayuntamiento de Madrid. He is presently translating Retana’s other landmark works, Vida y Escritos del Dr. José Rizal and the massive Aparato Bibliográfico de la Historia General de Filipinas.

About José Víctor Z. Torres

The esteemed history professor responsible for the history of the Philippine press in the book is José Víctor Z. Torres. He is a multi-awarded writer, Palanca award-winning playwright and essayist. An associate professor at the History Department of the De La Salle University, Manila, he earned his PhD in history from the University of Santo Tomás Graduate School and is the author and editor of works on Philippine history and culture and a contributor of historical and cultural articles to local magazines and journals.

The esteemed history professor responsible for the history of the Philippine press in the book is José Víctor Z. Torres. He is a multi-awarded writer, Palanca award-winning playwright and essayist. An associate professor at the History Department of the De La Salle University, Manila, he earned his PhD in history from the University of Santo Tomás Graduate School and is the author and editor of works on Philippine history and culture and a contributor of historical and cultural articles to local magazines and journals.

His book "Ciudad Murada: A Walk Through Historic Intramuros" (Vibal Publishing) won the National Book Award for Travel Writing in 2006. In 2017, his collection of essays "To the Person Sitting in Darkness and Other Footnotes in Philippine History" was awarded the National Book Award for Essays in English.

His book "Ciudad Murada: A Walk Through Historic Intramuros" (Vibal Publishing) won the National Book Award for Travel Writing in 2006. In 2017, his collection of essays "To the Person Sitting in Darkness and Other Footnotes in Philippine History" was awarded the National Book Award for Essays in English.

ADVERTISEMENT

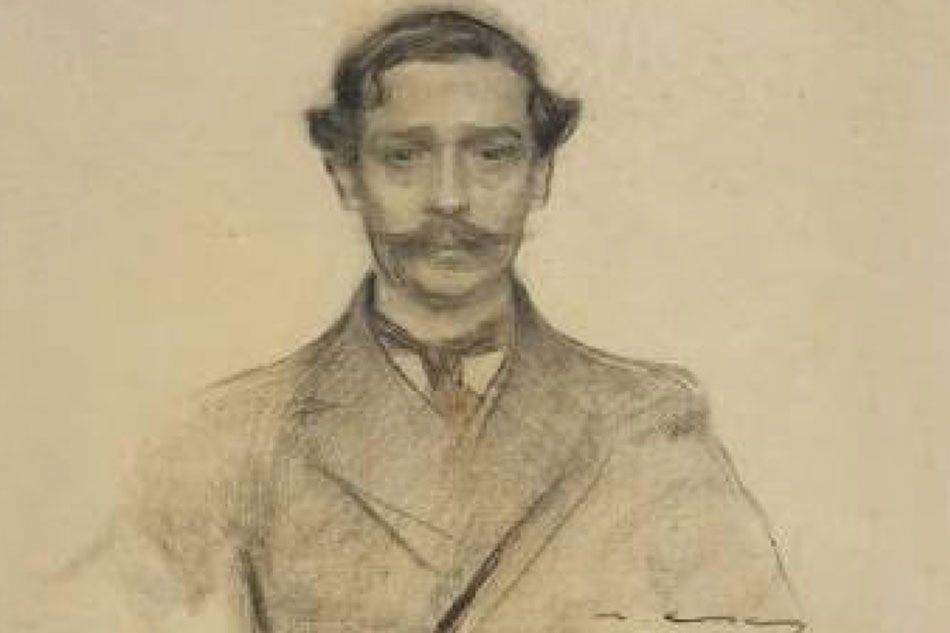

About Wenceslao E. Retana

Wenceslao Emilio Retana y Gamboa (1862–1924) was the leading 19th century Spanish scholar on the Philippines and a consummate bibliophile. Arriving in the Philippines in 1884, he was a witness to the raging conflict in the Spanish colony between the friars and colonial authorities who desperately held on to the status quo against those who advocated reform and even separatism. Returning to Spain in 1890, he founded an anti-Solidaridad periodical to combat the increasingly nationalistic propaganda of Filipino intellectuals.

Wenceslao Emilio Retana y Gamboa (1862–1924) was the leading 19th century Spanish scholar on the Philippines and a consummate bibliophile. Arriving in the Philippines in 1884, he was a witness to the raging conflict in the Spanish colony between the friars and colonial authorities who desperately held on to the status quo against those who advocated reform and even separatism. Returning to Spain in 1890, he founded an anti-Solidaridad periodical to combat the increasingly nationalistic propaganda of Filipino intellectuals.

As a deputy in the Spanish parliament and an active journalist, he debated the Philippine Revolution as it raged in two stages. A contemporary and erstwhile enemy of Filipino hero José Rizal, Retana publicly retracted his anti-Filipino thoughts by penning the first monumental biography of the Filipino national hero as a spiritual expiation of what he considered as Spain’s gravest mistake.

As a deputy in the Spanish parliament and an active journalist, he debated the Philippine Revolution as it raged in two stages. A contemporary and erstwhile enemy of Filipino hero José Rizal, Retana publicly retracted his anti-Filipino thoughts by penning the first monumental biography of the Filipino national hero as a spiritual expiation of what he considered as Spain’s gravest mistake.

Get your copy of El Periodismo Filipino available now thru shop.vibalgroup.com .

Get your copy of El Periodismo Filipino available now thru shop.vibalgroup.com .

-----------------------------------------------------

-----------------------------------------------------

The author is an economist, businessman, MYX/Awit award-winning media producer and Kala band guitarist.

The author is an economist, businessman, MYX/Awit award-winning media producer and Kala band guitarist.

ADVERTISEMENT

"JPnomics" discusses the author's views on pop-culture, economics, music, travel, history, science and technology.

"JPnomics" discusses the author's views on pop-culture, economics, music, travel, history, science and technology.

For questions, features and comments, e-mail him at jptanchanco@yahoo.com or tanchancotrimediaproductions@yahoo.com

For questions, features and comments, e-mail him at jptanchanco@yahoo.com or tanchancotrimediaproductions@yahoo.com

Read More:

blog roll

john paul tanchanco

JPnomics

Philippine journalism

book review

history

Philippine Press

El Periodismo Filipino

Jaime Marco

Vibal

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT