ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group

ABS-CBN News Digital Media

Surrender and die

Under Chapter III, Article 13, Paragraph 7 of the Revised Penal Code, one’s criminal liability is mitigated if the offender voluntarily surrenders to a person in authority or its agents.

But 16 of the victims were killed despite submitting themselves to the police, according to the accounts of families and witnesses.

One of them was suspected drug pusher, Eric Caliclic, 37, who was killed in his shanty under a bridge in Binondo, Manila on July 20.

Three neighbors interviewed by ABS-CBN News said they heard Caliclic pleading to the police not to shoot him.

Who are your friends?

They said that about 10 members of the MPD’s Station Anti-Illegal Drug Special Operation Task Unit and Intelligence Unit barged into Caliclic’s home at around 4 p.m. and first sent his live-in partner Evangeline Pinera outside.

The police interrogated Caliclic on the whereabouts of another pusher, but Caliclic refused to divulge anything because the pusher might kill him.

Two of his neighbors said they heard Caliclic wanting to surrender but one of the policemen instead shot him.

“Sabi niya susuko na siya,” said one of neighbors, “pero bakit pa pinatay nila?”

Caliclic died of multiple gunshot wounds in a buy-bust operation after firing at the police, the spot report dated July 20 showed.

There was no official report that would reinforce suspicions that he was shot in the mouth. By August, his body had been kept in a morgue. No relative has come forward to claim it.

No room to swing a cat

Thirty-three of the victims died in the confines of their homes that were so enclosed there was no room to swing a cat inside, so to speak.

Some were as small as about five square meters, like the house of Carlito Santos alias Kalbo, 43, in Balintawak, Quezon City.

Santos’ sister, Evelyn, showed ABS-CBN News the room where he was killed. It was part of the strip of shanties that stood at the back of the Balintawak Public Market made of scrap wooden boards. The boards looked so fragile a strong wind could crumble it anytime.

The room was too small that only a single-sized bed could fit. The walls were used as cabinets, with clotheslines connected from one end to another. Not even Evelyn, who stood about less than five feet, could stand up straight or stretch her arms wide inside.

No room to fight back

“Lalaban ba yung kapatid ko ang liit-liit nung tao, ilang pulis ang sumugod?” she said.

But the police record in Quezon City showed a police team was conducting a One-Time, Big-Time Operation and Oplan Kapak (QC’s version of Oplan Tokhang) when Santos saw them and fired at them. The police retaliated, killing Santos on the spot.

Santos was said to be No. 2 in the La Loma Police Station’s Most Wanted Drug List.

Evelyn said her brother bore gunshot wounds in the right part of his neck and chest. His death certificate did not show the cause of death. The family failed to get the autopsy report from the funeral services.

One man, 10 gunshot wounds

Many of the victims, according to their death certificates and autopsy reports, were shot multiple times—in the head, chest, and upper parts of their bodies. Some suffered as many as eight to 10 shots; the people they left behind called it “inhumane killing.”

Suspected drug pusher Florentino Santos, 44, suffered 10 gunshot wounds in his body, mostly in the trunk, said one of his relatives who saw him first at the morgue.

“Hindi tama iyon, kasi isang [beses] lang, mamamatay na tao e,” he said. “Kagaya noon, malapitan, binaril mo rito [sa harap] tagos doon [sa likod]…kaya sampu ang butas [sa katawan] e."

Santos was found dead in a nearby village a few hours after he left his house in Barangay Tiaong, Guiguinto, Bulacan.

Santos had been under surveillance for two weeks. Police assets had successfully bought shabu from him twice on July 18 and 20.

In a spot report of Guiguinto police dated July 21, a poseur-buyer was about to buy shabu from Santos, but Santos shot the buyer upon sight. It would have been the third time.

Santos died of gunshot wounds in the trunk and left upper extremity, his death certificate showed.

Overkill

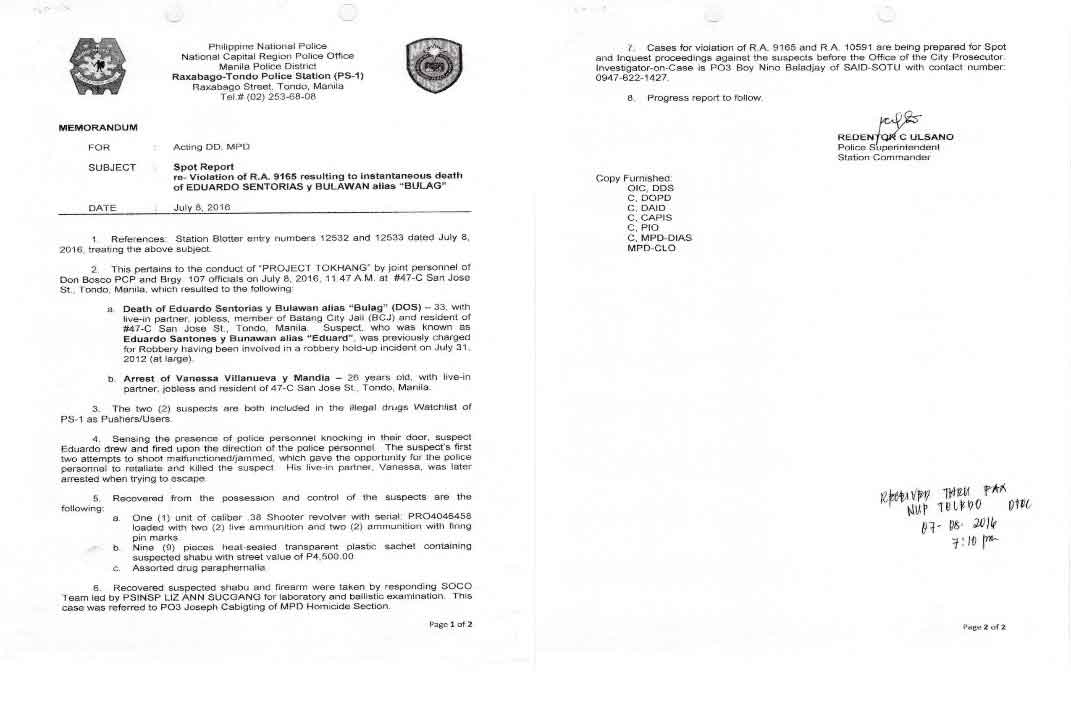

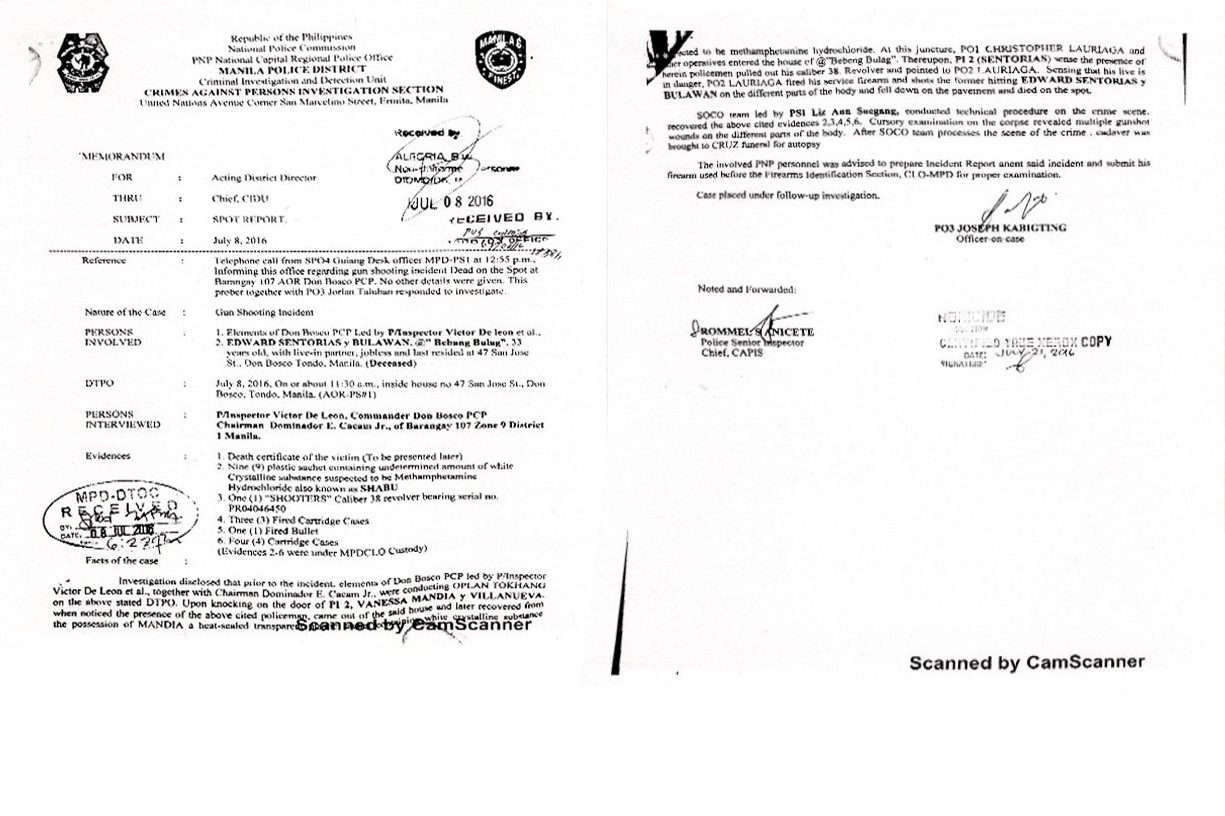

Yolanda Sentorias, mother of alleged drug pusher Eduardo Sentorias, also lamented how her son was liquidated. It was overkill, she said.

Sentorias, 33, was killed on July 8 in an Oplan Tokhang by joint teams of the Don Bosco Police Community Precinct and officials of Barangay 107, Tondo, Manila.

According to the autopsy report, the suspect was shot four times: one in the right forehead that exited through the left portion of the back of the head; two in the trunk; and one in the left hand.

One dead, two different reports

The ABS-CBN team obtained two spot reports from the MPD Raxabago-Tondo Police Station 1 and the MPD-Criminal Investigation and Detection Unit. They had different versions of his death.

The Station 1 reported that after the authorities knocked on the door, Sentorias came out of the house and opened fire, prompting the police to retaliate and kill him.

The CIDU reported it was Sentorias’ partner Vanessa Mandia, who came out of the house, and the police got from her a sachet of shabu. The operatives then went into the house, but Sentorias greeted them with bullets.

But in reality, the police dragged Mandia and her two-year old child out of the house, leaving Sentorias alone inside, Sentorias’ mother Yolanda said, quoting Mandia.

“Hinaltak siya [Mandia] ng pulis palabas, tapos yun na, wala na, pinatay na ‘yung anak ko.”

Dead man had no gun

Some of the victims could not have fought back, according to their relatives, because they didn’t have guns.

Like Sentorias’ mother, Roberto Dominguez’s mother raised doubts about her son fighting back. How could my son engage the police in a gunfight if he had no gun? she asked.

Teresita Dominguez said it was impossible for her son, eldest of her nine children, to own a gun because he was scared of it.

Police recovered from Dominguez a .38-caliber loaded with three bullets and two fired cartridges and five sachets of suspected shabu.

“Kutsilyo pwede pa, kasi nagkakatay ng baboy yun,” she said.

Police recovered from 30 other slain suspects .38-revolver each, records showed. Until 2011, a .38-caliber revolver was once the police service firearm.

In a 2011 report, the PNP said it had to replace the .38-caliber service firearm because of its unreliability: it often misfires and unlike semiautomatic pistols, revolvers’ six cartridges had to be replaced individually.

It was said to be the drug dealers’ weapon of choice because it could easily be obtained in the black market for as low as P3,000.

Where the gun came from

But relatives of 38 victims said the dead did not own a gun. Most of the fatalities only lived by the day and did not have the means to buy such firearm. And if they ever had one, they would have had pawned it to buy food for their families.

“Paano magkakabaril yan eh pambili nga ng gatas ng anak niya wala e, baril pa kaya?” said one of Carlito Santos’ neighbors.

A neighbor of suspected drug peddler Celso Guites alias Picos, 48, said she saw members of Airport Police Community Precinct place a gun beside the victim inside his house in Barangay 193, Pasay City, shortly after Guites was gunned down.

The usual suspect

Guites had been in and out of the prison thrice for drugs possession. He was released on bail the last time in February, according to his family.

Guites had changed his ways, the family said, but the police didn’t believe it.

“Sir, nagbago na ko Sir. Di na ko (tulak) ng droga, ang asawa ko lang po,” the neighbor quoted Guites telling the police.

A policeman then took out a .45-caliber gun and told him to hold it. He refused and instead raised his hands in the air. In response, the policeman shot him dead.

“Nagmamakaawa na si Picos,” the neighbor said. “'Sir, sir,’ hindi nila talaga pinakinggan... Wala silang awa. Walang kalaban-laban.”

In a report dated July 17, the Pasay City police said Guites was killed in an Oplan Tokhang after refusing to surrender.

He was shot multiple times in the trunk, the death certificate showed.

In handcuffs

But seven of the 50 cases had guns, according to the families of the victims.

One of them was Rio Awa alias Dodong, 31, of Sta. Ana, Taytay, Rizal.

Awa had a gun, but his family expressed doubts that he was able to use it at all because his hands were handcuffed from behind.

On the morning of July 24, members of the Rizal PNP’s Provincial Intelligence Branch and Special Operations Unit apprehended Awa while he was walking on the street. He was handcuffed, witnesses said, and brought inside his shack where he was killed minutes later.

"Paano yun nanlaban? Eh kitang kita namin dito nakaposas sa likod,” a witness said.

Awa was shot in the head, his death certificate showed. His sister, Marianne Awa, said his neck bore a slit.

“Okay lang naman sana kung binaril lang,” Marianne said. “Pero nakita ko parang may [hiwa] pa dito sa leeg. Yun yung hinanakit ko nung pagkatingin ko. Sumigaw talaga ako eh.”

According to the spot report, Awa was killed in a buy-bust operation. Awa reportedly drew his gun and fired at the operatives who, in turn, shot and killed him.

Marianne said he should have been given a second chance to turn his life around. He was just new to the illegal drug trade, around six months, she said, and he was not the big-time peddler like the authorities said he was.

“Dapat naman kasi sana kinilala muna nila yung isang tao na kung talagang totoong big time,” Marianne said.

Fighting the police

Many of the families interviewed by ABS-CBN News wanted to sue the police for depriving their relatives of their right to due process.

Still, many felt heavily burdened trying to prove and sustain the suits. Where would they get the money? What if they get killed, too?

These were the questions running through Niolyn Garcia’s mind.

When an ABS-CBN News team arrived at her home in Sta. Rosa, Laguna on August 26 for an interview, Niolyn thought the news team was the answer to her prayers.

Her son, 23-year-old Jerome Garcia, was killed in an alleged shootout on July 1 with a team of Sta. Rosa policemen wanting to serve an arrest warrant on his companion Ryan Roy Barroga, a murder suspect.

"Araw-araw pinagdadasal ko na sana isang araw may kakatok diyan sa pinto namin, tetestigo at sasabihin kung ano talaga ang nangyari sa anak ko,” the mother said.

In the spot report, the Sta. Rosa City Police said that Garcia fired at them while they were serving the warrant. Both Garcia and Barroga died on the spot.

Good guy, bad company

But Niolyn said her son was merely a collateral damage--Jerome was never involved in drugs. He was a pedicab driver trying to help her and her husband make both ends meet for their family of seven, she said.

He was just too friendly, she added, that he tagged along with people, even those he barely knew, like Barroga.

No witness, no case

The absence of witnesses against the police made their ordeal worse. Some told her that they saw her son pleading and surrendering before getting killed—but when she asked them to help them file a case, they turned it down out of fear.

“Gusto naming [malaman] kung sino talaga yung nakakita, ano ba talaga ang totoong nangyari, kaso walang makapagsabi sa amin,” she said.

Like Niolyn, questions still lingered in the mind of Cristina Francisco, two months after her son, Henry Francisco, 37, was killed in a buy-bust operation in Bagbaguin, Valenzuela City on July 20.

Death at her doorsteps

Francisco never thought she would ever worry about things happening around her, especially the government’s war on drugs, the casualties and effects of which could only be seen on television, she said.

Until it happened to her own son.

“Apektado na ako,” she said. “Noon ko lang naisip sabi ko, bakit diyos ka ba, Presidente Digong, at kukunin mo yung buhay ng anak ko?”

No chance to change

If the victims had, indeed, committed crimes, then they should have been rehabilitated and reintegrated into society, Francisco said.

They could have turned their lives around if only they had been allowed to, she said. But how could these people change now they are dead?

For the families of the thousands killed in the war on drugs, change would never come.