Street art as an expression of freedom in Germany and the Philippines | ABS-CBN

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

Street art as an expression of freedom in Germany and the Philippines

Street art as an expression of freedom in Germany and the Philippines

Jeffrey Hernaez,

ABS-CBN News

Published Oct 05, 2018 07:28 PM PHT

BERLIN, Germany - In the Philippine setting, graffiti is still traditionally seen as vandalism, where public property is defaced by random scribbles written by juvenile delinquents, or by protesters writing their political slogans.

BERLIN, Germany - In the Philippine setting, graffiti is still traditionally seen as vandalism, where public property is defaced by random scribbles written by juvenile delinquents, or by protesters writing their political slogans.

There are already some instances where companies hire artists to create murals on their buildings’ walls and the walkways of Makati City feature different artistic styles, but graffiti as street art is still a small movement in the country.

There are already some instances where companies hire artists to create murals on their buildings’ walls and the walkways of Makati City feature different artistic styles, but graffiti as street art is still a small movement in the country.

In contrast, Europe has embraced street art as a medium of expression on a large scale.

In contrast, Europe has embraced street art as a medium of expression on a large scale.

As Germany celebrated the fall of the Berlin Wall last Wednesday, one would marvel at the transformation it has undergone from being a physical and emotional barrier between a divided country to becoming a symbol of unity all over the world.

As Germany celebrated the fall of the Berlin Wall last Wednesday, one would marvel at the transformation it has undergone from being a physical and emotional barrier between a divided country to becoming a symbol of unity all over the world.

ADVERTISEMENT

I was only 6 when the wall was torn down, too young to realize the impact of such a global event, but to see the resulting expression of freedom through the art that has been installed through the length of the East Side Gallery is a breathtaking and emotional trip through that momentous event.

I was only 6 when the wall was torn down, too young to realize the impact of such a global event, but to see the resulting expression of freedom through the art that has been installed through the length of the East Side Gallery is a breathtaking and emotional trip through that momentous event.

The remnants of the wall have become a gallery, where people can gather and appreciate the murals that have become symbols of freedom.

The remnants of the wall have become a gallery, where people can gather and appreciate the murals that have become symbols of freedom.

At 1.3 kilometers of painstakingly-created graffiti, it is a shining example of how art can bring people together.

At 1.3 kilometers of painstakingly-created graffiti, it is a shining example of how art can bring people together.

Some of the more known works of art posted on the Wall are "The Kiss" showing the Socialist Fraternal Kiss between Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and East German President Erich Honecker, with the artist Dmitri Vrubel captioning it, “My God, Help Me Survive This Deadly Love.”

Some of the more known works of art posted on the Wall are "The Kiss" showing the Socialist Fraternal Kiss between Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and East German President Erich Honecker, with the artist Dmitri Vrubel captioning it, “My God, Help Me Survive This Deadly Love.”

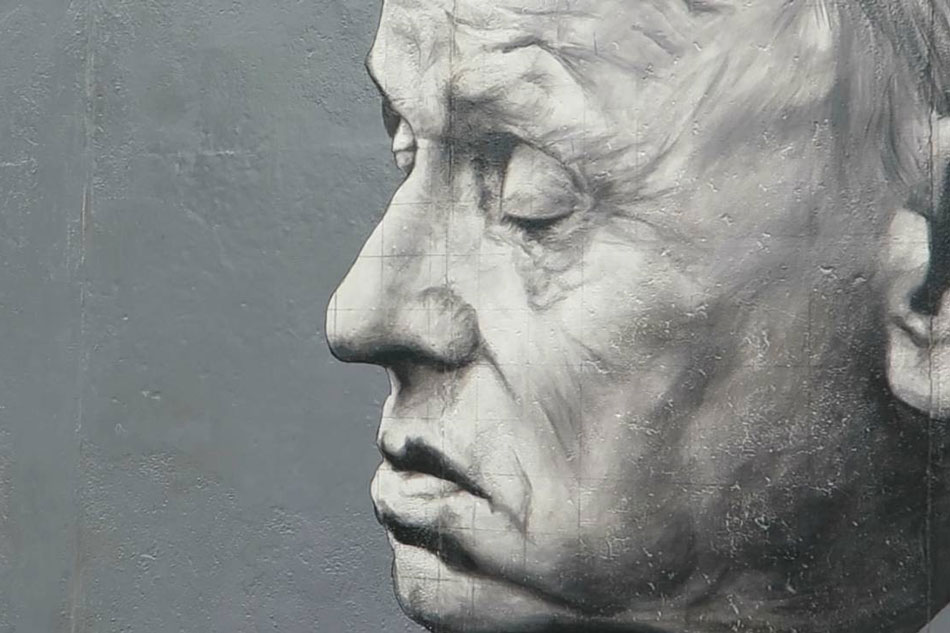

On a more empowering note is "Danke, Andrej Sacharow," an arresting portrait of a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, and human rights activist who stood for freedom and liberty, also by Vrubel and Viktoria Timofeeva.

On a more empowering note is "Danke, Andrej Sacharow," an arresting portrait of a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, and human rights activist who stood for freedom and liberty, also by Vrubel and Viktoria Timofeeva.

ADVERTISEMENT

In contrast to the solemnity of the two other works, "Cartoon Heads" by French artist Thierry Noir, who is said to make it his mission to “demystify the wall” as his revolutionary act, with his brightly colored exaggerated heads is doing just that – transforming the edifice by lending a bit of levity to something so awful.

In contrast to the solemnity of the two other works, "Cartoon Heads" by French artist Thierry Noir, who is said to make it his mission to “demystify the wall” as his revolutionary act, with his brightly colored exaggerated heads is doing just that – transforming the edifice by lending a bit of levity to something so awful.

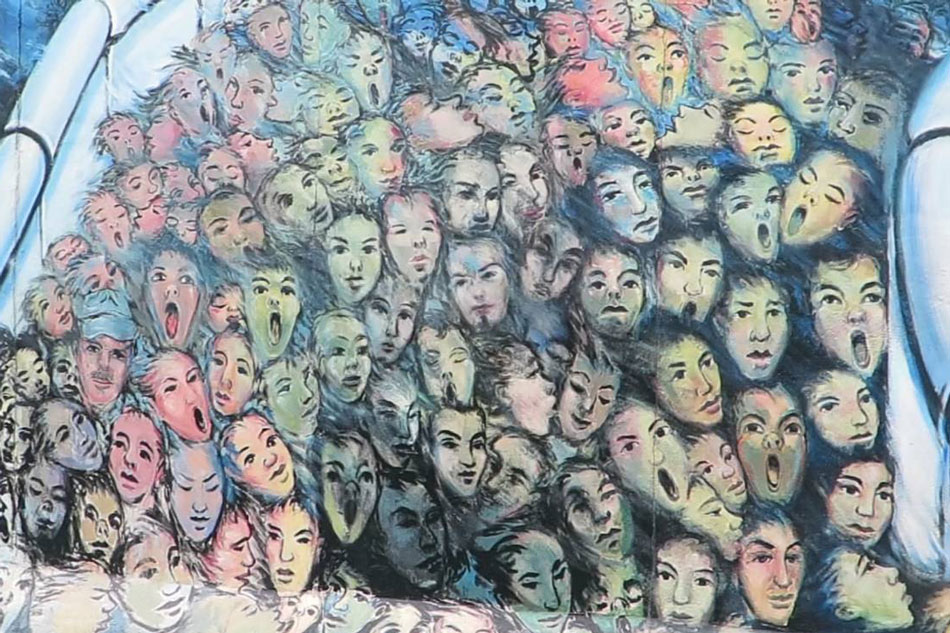

Perhaps the most succinct installment on the Wall is "It’s Happened in November" by Berlin artist Kani Avi. It is an abstract that depicts the gamut of emotions from East German faces as they cross into West Germany after the Wall fell. Checkpoint Charlie, as shown in the painting, was a myriad of faces full of hope – or uncertainty as they crossed over to the free world.

Perhaps the most succinct installment on the Wall is "It’s Happened in November" by Berlin artist Kani Avi. It is an abstract that depicts the gamut of emotions from East German faces as they cross into West Germany after the Wall fell. Checkpoint Charlie, as shown in the painting, was a myriad of faces full of hope – or uncertainty as they crossed over to the free world.

If the Berlin Wall was built to divide two different ideologies (East and West Berlin), now the remnants of the wall are now covered with graffiti that challenges norms and ideas, and unites not only Germany, but the rest of the world that is still currently struggling toward integration and lasting peace.

If the Berlin Wall was built to divide two different ideologies (East and West Berlin), now the remnants of the wall are now covered with graffiti that challenges norms and ideas, and unites not only Germany, but the rest of the world that is still currently struggling toward integration and lasting peace.

It shows that something physical like the Wall, which was built to divide people, can now be seen as a canvas for expression, where graffiti and other forms of modern art -- even those that are posted online – are just as effective in portraying emotions and movements as those that were created by the Masters.

It shows that something physical like the Wall, which was built to divide people, can now be seen as a canvas for expression, where graffiti and other forms of modern art -- even those that are posted online – are just as effective in portraying emotions and movements as those that were created by the Masters.

If these works were framed and hung within the hushed confines of the Louvre in Paris or the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in New York, they might have been less effective as tools to portray truth and reality. The grittiness and perils associated with such bold acts of art might lose something essential in its spirit of sheer subversiveness. This is why these deserve to be preserved in its location, as a reminder of what can happen in an imbalance of power, where freedom and lives are at stake.

If these works were framed and hung within the hushed confines of the Louvre in Paris or the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in New York, they might have been less effective as tools to portray truth and reality. The grittiness and perils associated with such bold acts of art might lose something essential in its spirit of sheer subversiveness. This is why these deserve to be preserved in its location, as a reminder of what can happen in an imbalance of power, where freedom and lives are at stake.

ADVERTISEMENT

Graffiti in its truest form as art has been employed over the world effectively even to this day. Examples are everywhere, with artist provocateur Banksy gaining worldwide renown (and notoriety) for his humorously subversive works.

Graffiti in its truest form as art has been employed over the world effectively even to this day. Examples are everywhere, with artist provocateur Banksy gaining worldwide renown (and notoriety) for his humorously subversive works.

While in the Philippines, larger, more noticeable examples of street art is mostly commercialized and commissioned. In these cases, the truest essence has been diluted by a need to conform to commercialism instead of the clandestine act of provocative vandalism that graffiti is viewed as.

While in the Philippines, larger, more noticeable examples of street art is mostly commercialized and commissioned. In these cases, the truest essence has been diluted by a need to conform to commercialism instead of the clandestine act of provocative vandalism that graffiti is viewed as.

But there is a small guerrilla band of Filipino artists who make it their mission to beautify the mean streets of Manila with their works, spreading social-themed messages as they do so.

But there is a small guerrilla band of Filipino artists who make it their mission to beautify the mean streets of Manila with their works, spreading social-themed messages as they do so.

One particular example is Kookoo Ramos, whose works not only beautify but through her celebration of the female face and form, challenge male-dominated norms.

One particular example is Kookoo Ramos, whose works not only beautify but through her celebration of the female face and form, challenge male-dominated norms.

Whether commissioned or done on the sly, these Filipino artists are serving a need in the country – bringing visual art to the masses. Traditionally, Filipinos are not museum-goers, and their exposure to the art is limited, at most.

Whether commissioned or done on the sly, these Filipino artists are serving a need in the country – bringing visual art to the masses. Traditionally, Filipinos are not museum-goers, and their exposure to the art is limited, at most.

ADVERTISEMENT

With street art executed by passionate artists, they become exposed to art that brings messages that reflect society. As such, graffiti symbolizes freedom, whether it is in the wide, well-swept streets of Berlin or the rousing cacophony that is Manila.

With street art executed by passionate artists, they become exposed to art that brings messages that reflect society. As such, graffiti symbolizes freedom, whether it is in the wide, well-swept streets of Berlin or the rousing cacophony that is Manila.

WATCH: The fall of the Berlin Wall and how it changed the history of a great nation. Philippine Chargé d' Affaires Lillibeth Pono tells us what the Philippines can learn from the historic event that was inspired by the peaceful EDSA revolution. #GermanUnionDay #GoetheCloseUp pic.twitter.com/xWxP95lkas

— jeff hernaez (@jeffreyhernaez) October 4, 2018

WATCH: The fall of the Berlin Wall and how it changed the history of a great nation. Philippine Chargé d' Affaires Lillibeth Pono tells us what the Philippines can learn from the historic event that was inspired by the peaceful EDSA revolution. #GermanUnionDay #GoetheCloseUp pic.twitter.com/xWxP95lkas

— jeff hernaez (@jeffreyhernaez) October 4, 2018

This article was written as part of the Goethe-Institut’s Close Up Journalist’ exchange programme. More information can be found at www.goethe.de/nahaufnahme and at #goethecloseup.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT