Art in the time of corona: How 3 Angono artists are surviving the pandemic | ABS-CBN

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

Art in the time of corona: How 3 Angono artists are surviving the pandemic

Art in the time of corona: How 3 Angono artists are surviving the pandemic

Celine Murillo

Published Oct 18, 2020 01:50 PM PHT

In his studio on the banks of the Angono River, Nemesio R. Miranda Jr. finds solace.

In his studio on the banks of the Angono River, Nemesio R. Miranda Jr. finds solace.

Just like most Filipinos, Nemiranda – as he has come to be known – has been forced to stay at home since quarantine began in March. But the 71-year-old painter and sculptor wouldn’t exactly call it “being stuck”.

Just like most Filipinos, Nemiranda – as he has come to be known – has been forced to stay at home since quarantine began in March. But the 71-year-old painter and sculptor wouldn’t exactly call it “being stuck”.

With events canceled and meetings postponed, Nemiranda found himself with so much free time that in between tending to his riverside garden and games of chess, he picks up either his brush or his chisel to do what he does best: create. A quartet of floor-to-ceiling murals – all birthed in the last six months – stands in full display inside his studio.

With events canceled and meetings postponed, Nemiranda found himself with so much free time that in between tending to his riverside garden and games of chess, he picks up either his brush or his chisel to do what he does best: create. A quartet of floor-to-ceiling murals – all birthed in the last six months – stands in full display inside his studio.

“Everything that happens is an inspiration,” he quips.

“Everything that happens is an inspiration,” he quips.

ADVERTISEMENT

Tucked in one corner of the studio, the first of his recent creations is a somber depiction of a disaster and an advent of an upending: the Taal Eruption and the very first days of the coronavirus outbreak.

Tucked in one corner of the studio, the first of his recent creations is a somber depiction of a disaster and an advent of an upending: the Taal Eruption and the very first days of the coronavirus outbreak.

The second is laden with his trademark style – bucolic in simplicity, rural, Filipino. At first glance, it seems like a typical day in Angono – fishermen, kids flying kites, women bathing in the river – but then you see an oddity that is now commonplace: face masks. In this piece, even the higantes – the town’s “mascot” – wear them.

The second is laden with his trademark style – bucolic in simplicity, rural, Filipino. At first glance, it seems like a typical day in Angono – fishermen, kids flying kites, women bathing in the river – but then you see an oddity that is now commonplace: face masks. In this piece, even the higantes – the town’s “mascot” – wear them.

The third of four feels almost like a climax. A culmination of some sort. Strewn across the canvas is Nemiranda’s Philippines in a pandemic: an anthropomorphized coronavirus clutching at the people, medical frontliners, Pope Francis praying, recognizable politicians here in there (whether done in earnest or in humor, he didn’t say). It looked like an attempt to consolidate. Or, perhaps, to process.

The third of four feels almost like a climax. A culmination of some sort. Strewn across the canvas is Nemiranda’s Philippines in a pandemic: an anthropomorphized coronavirus clutching at the people, medical frontliners, Pope Francis praying, recognizable politicians here in there (whether done in earnest or in humor, he didn’t say). It looked like an attempt to consolidate. Or, perhaps, to process.

“Wars, catastrophes,” he says. “These are all subject matters.”

“Wars, catastrophes,” he says. “These are all subject matters.”

Macabre may be the subjects of the first three, but his latest work seem to have moved away from the pall of the pandemic, into a time sans physical distancing and face masks. The focal point of the yet-to-be finished piece is the separation of Angono from Binangonan and Taytay. There’s former president Manuel Quezon, who decreed the township, surrounded by a medley of conviviality one can only experience in the art capital. It is both celebratory and nostalgic.

Macabre may be the subjects of the first three, but his latest work seem to have moved away from the pall of the pandemic, into a time sans physical distancing and face masks. The focal point of the yet-to-be finished piece is the separation of Angono from Binangonan and Taytay. There’s former president Manuel Quezon, who decreed the township, surrounded by a medley of conviviality one can only experience in the art capital. It is both celebratory and nostalgic.

Taking into account this collection, as well as the numerous other projects Nemiranda has set out to do – including an animatronic Higantes – one can infer that he has been astonishingly productive.

Taking into account this collection, as well as the numerous other projects Nemiranda has set out to do – including an animatronic Higantes – one can infer that he has been astonishingly productive.

“I try to spend my days wisely,” he shares. “The world needs a vaccine? Well, I don’t know how to do that. So I focus here” – he gestures to his artworks – “on things I can control.”

“I try to spend my days wisely,” he shares. “The world needs a vaccine? Well, I don’t know how to do that. So I focus here” – he gestures to his artworks – “on things I can control.”

Nemiranda’s case is aspirational. One can even say enviable. The concept of “art block” doesn’t seem to faze this man. Perhaps it was his discipline. Or his years of experience. Maybe it’s the inherent “independent” nature of his art. Or it could just be sheer privilege. Maybe all of the above.

Nemiranda’s case is aspirational. One can even say enviable. The concept of “art block” doesn’t seem to faze this man. Perhaps it was his discipline. Or his years of experience. Maybe it’s the inherent “independent” nature of his art. Or it could just be sheer privilege. Maybe all of the above.

But not all artists thrive in solitude.

But not all artists thrive in solitude.

Ferdinand Pitogo, 31, has been a musician for most of his life. At the age of eight, he joined one of Angono’s many marching bands and learned the basics of brass instruments under his uncle’s tutelage. He started with the trumpet, and grew to love the resonant sound of the trombone.

Ferdinand Pitogo, 31, has been a musician for most of his life. At the age of eight, he joined one of Angono’s many marching bands and learned the basics of brass instruments under his uncle’s tutelage. He started with the trumpet, and grew to love the resonant sound of the trombone.

After studying music at the University of the Philippines and a five-year stint as a band member in Hong Kong Disneyland, Pitogo found himself back in his hometown.

After studying music at the University of the Philippines and a five-year stint as a band member in Hong Kong Disneyland, Pitogo found himself back in his hometown.

“We are lucky to have a culture of music and art in Angono,” he declares. “We’re a small town, but we have eight marching bands – some towns don’t even have one!”

“We are lucky to have a culture of music and art in Angono,” he declares. “We’re a small town, but we have eight marching bands – some towns don’t even have one!”

He is a full-time musician and conductor, offering private lessons to Korean expats and doing “combo” gigs in bars and events. Under normal circumstances, Pitogo would have already been busy with Christmas concerts and public performances during the “ber" months. However, as the pandemic brought large social gatherings to a halt, the gigs and events also stopped coming.

He is a full-time musician and conductor, offering private lessons to Korean expats and doing “combo” gigs in bars and events. Under normal circumstances, Pitogo would have already been busy with Christmas concerts and public performances during the “ber" months. However, as the pandemic brought large social gatherings to a halt, the gigs and events also stopped coming.

In spite of this, Pitogo is lucky to have his income supplemented by rental fees from an apartment building he was able to put up during his Disneyland days. But to him, the brunt of COVID-19 was not so much on his livelihood but on his music.

In spite of this, Pitogo is lucky to have his income supplemented by rental fees from an apartment building he was able to put up during his Disneyland days. But to him, the brunt of COVID-19 was not so much on his livelihood but on his music.

“Practice has always been part of my daily routine,” he says. “So nothing has changed in that aspect.”

“Practice has always been part of my daily routine,” he says. “So nothing has changed in that aspect.”

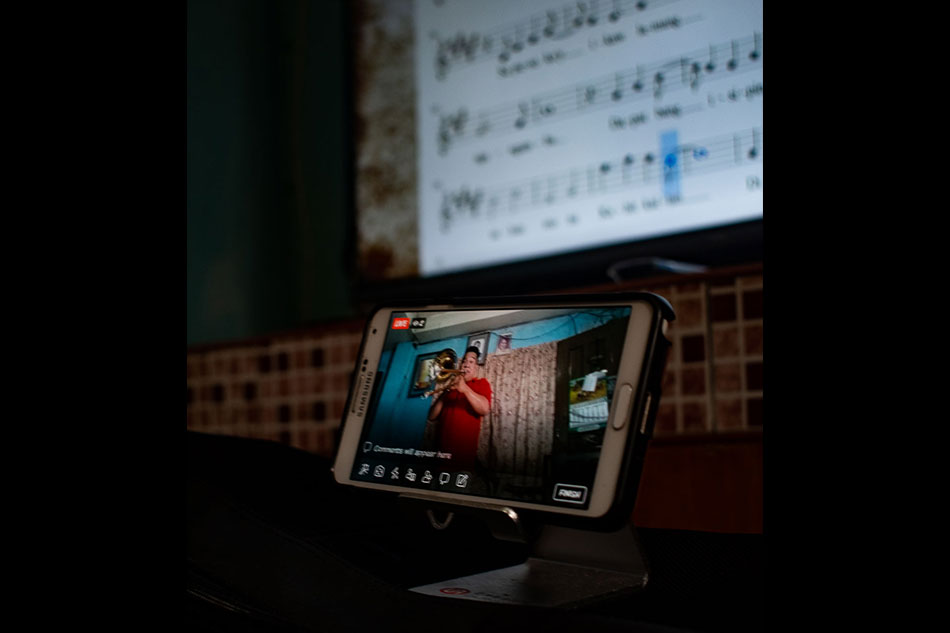

Most days, you’ll find him playing along backing tracks from YouTube. The video streaming platform provides a wealth of resources to occupy him for hours. But by himself, the sounds he makes – while beautiful – seems almost lonely.

Most days, you’ll find him playing along backing tracks from YouTube. The video streaming platform provides a wealth of resources to occupy him for hours. But by himself, the sounds he makes – while beautiful – seems almost lonely.

His is a music that sounds best when enmeshed with others’. According to him, the “color” is more vibrant when he performs this way. The tone more full. The dynamics completely different.

His is a music that sounds best when enmeshed with others’. According to him, the “color” is more vibrant when he performs this way. The tone more full. The dynamics completely different.

Performing with others is a craft in itself. There are cues and nuances to follow, so to be unable to go out and do this is a great source of frustration for musicians like Ferdinand.

Performing with others is a craft in itself. There are cues and nuances to follow, so to be unable to go out and do this is a great source of frustration for musicians like Ferdinand.

“I am used to performing with an ensemble,” he says. “That’s 50 musicians.”

“I am used to performing with an ensemble,” he says. “That’s 50 musicians.”

Public performances are also something he yearns for. While he often goes live on social media, he maintains it’s a different experience when the audience is physically there with him. The pre-show jitters can be unsettling, but it’s a kind of rush that he misses.

Public performances are also something he yearns for. While he often goes live on social media, he maintains it’s a different experience when the audience is physically there with him. The pre-show jitters can be unsettling, but it’s a kind of rush that he misses.

Fortunately, when the restrictions eased up in Rizal last September, the local government offered Pitogo a chance to perform. Every Monday, a flag ceremony held in the Angono Municipal Square allows him to play his music the way it was intended.

Fortunately, when the restrictions eased up in Rizal last September, the local government offered Pitogo a chance to perform. Every Monday, a flag ceremony held in the Angono Municipal Square allows him to play his music the way it was intended.

Well, almost.

Well, almost.

To comply with protocols, the ensemble was reduced to only 15 people. To Pitogo, this was better than nothing at all. He didn’t have a hard time finding willing musicians.

To comply with protocols, the ensemble was reduced to only 15 people. To Pitogo, this was better than nothing at all. He didn’t have a hard time finding willing musicians.

“We were all very happy to play together after five months.”

“We were all very happy to play together after five months.”

As Pitogo regains his rhythm, limited as it may be, 29-year-old Christopher “Tophee” Marquez refuses to settle.

As Pitogo regains his rhythm, limited as it may be, 29-year-old Christopher “Tophee” Marquez refuses to settle.

The conceptual photographer intends to ride the pandemic out, at least until he can create freely again.

The conceptual photographer intends to ride the pandemic out, at least until he can create freely again.

“I no longer take photographs just for the sake of it,” he says. “I don’t want to create just because there’s a sort of pressure.”

“I no longer take photographs just for the sake of it,” he says. “I don’t want to create just because there’s a sort of pressure.”

Marquez’s works are visual stories and preparing for it is no small matter. His sets are like stills from movies, conjured pretty much the same way.

Marquez’s works are visual stories and preparing for it is no small matter. His sets are like stills from movies, conjured pretty much the same way.

Drawing from a mental storyboard, he scouts for models and locations as well as props. Limited transportation modes and lockdown restrictions hinder this process, and he’s adamant he’d rather not do it if it’s not faithful to how he envisions it.

Drawing from a mental storyboard, he scouts for models and locations as well as props. Limited transportation modes and lockdown restrictions hinder this process, and he’s adamant he’d rather not do it if it’s not faithful to how he envisions it.

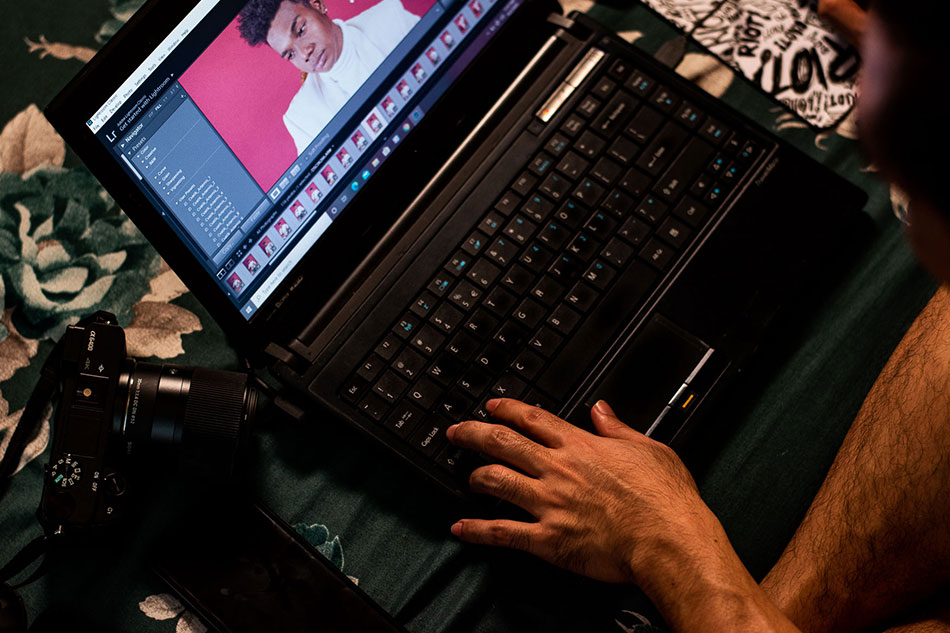

To compensate, Marquez either takes self-portraits or revisits his old works, giving them different post-processing treatments.

To compensate, Marquez either takes self-portraits or revisits his old works, giving them different post-processing treatments.

“But it feels limited and not really satisfying,” he admits.

“But it feels limited and not really satisfying,” he admits.

Marquez is well aware of the consequences of his holding back. While he used to have “trains of concepts” pre-pandemic, now, he says it’s just an empty railroad. He’s not bothered by this case of art block though, preferring to view it as “chilling.”

Marquez is well aware of the consequences of his holding back. While he used to have “trains of concepts” pre-pandemic, now, he says it’s just an empty railroad. He’s not bothered by this case of art block though, preferring to view it as “chilling.”

When not working from home as a programmer, he listens to music and watches films and series.

When not working from home as a programmer, he listens to music and watches films and series.

“Music and movies influence me a lot. They’re great sources of inspiration.”

“Music and movies influence me a lot. They’re great sources of inspiration.”

In this sense, Marquez’s no different from a lot of Filipinos. Like him, many have turned to these particular art forms to “process” what’s happening.

In a town like Angono, where artists of all kinds are aplenty, the stories of Nemiranda, Pitogo, and Marquez are the stories of many. Indeed, like Nemiranda, some have harnessed the tumultuous current events to power their creativity, churning piece after piece. Like Pitogo, some have plodded along and tried to stay afloat in solitude. While others, like Marquez, have chosen to come away from the water to dip their toes someplace else.

In this sense, Marquez’s no different from a lot of Filipinos. Like him, many have turned to these particular art forms to “process” what’s happening.

In a town like Angono, where artists of all kinds are aplenty, the stories of Nemiranda, Pitogo, and Marquez are the stories of many. Indeed, like Nemiranda, some have harnessed the tumultuous current events to power their creativity, churning piece after piece. Like Pitogo, some have plodded along and tried to stay afloat in solitude. While others, like Marquez, have chosen to come away from the water to dip their toes someplace else.

These different responses are riddled with subtleties that could very well involve economic class and privilege. It’s true – creating tends to be a self-centered act. Artists must (or mustn’t) make. They are, by necessity, selfish.

These different responses are riddled with subtleties that could very well involve economic class and privilege. It’s true – creating tends to be a self-centered act. Artists must (or mustn’t) make. They are, by necessity, selfish.

But in a time where a huge and impassible divide seemed to have wended its way across our nation, it might be important for artists to ask themselves this: do we make to connect or to isolate?

But in a time where a huge and impassible divide seemed to have wended its way across our nation, it might be important for artists to ask themselves this: do we make to connect or to isolate?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT